website watertownhistory.org

ebook History of Watertown, Wisconsin

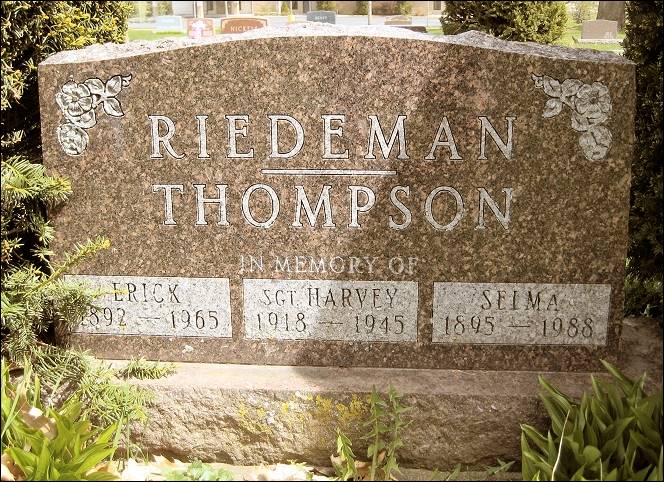

Harvey Riedeman

1918 - 1945

Ken Riedl

Ken Riedl

Father,

Sgt. Harvey Riedeman, Mother

Sgt.

Harvey Riedeman. Harvey was a member of

the 192nd Tank Battalion and was assigned to A Company.

The

company was originally a Wisconsin National Guard Tank Company from Janesville.

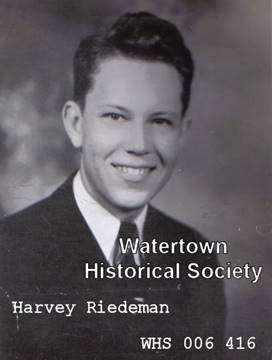

Contributed

photo of Harvey Riedeman. From the scrapbook of 1st Lt. Jacques Merrifield.

Merrifield

was an Illinois National Guardsman who went to the Philippines as a sergeant

and

received a battlefield commission.

From

what is known, the two men were

good

friends at Ft. Knox and in the Philippines.

1945

Watertown Daily Times, 09

28 1945

Staff

Sgt. Harvey H. Riedeman, Watertown's only prisoner of war of the Japanese, is

dead. Official word to that effect came here this morning in a message from the

office of the secretary of war.

The message

reached Watertown shortly after

"It

was one of the saddest things I ever had to do," Mr. Redstrom said. He

contacted Miss Marion Haney, local Red Cross representative, and informed her

of the fact, asking her to go to the Riedeman home, which she did.

Text of Message

It was

from Miss Haney that the Daily Times

secured the text of the message to Mr. and Mrs. Erick A. Riedeman,

"The

secretary of war asks me to inform you that your son, Staff Sgt., Harvey H.

Riedeman died aboard a Japanese transport while a prisoner of war on

Mrs.

Riedeman was too distraught to speak when sympathetic friends and neighbors

called. She broke down upon receipt of

the message. She had been hopeful that her son was alive and was looking for

the day when a message telling her of his safety would come to the home.

Instead, today there came the death message. Mr. Riedeman, a railroad man, was

out of the city when the message came. He was due to return this afternoon.

Friends Notified

The Daily Times dispatched a telegram to

Maj. Paul L. Ashton, a young army doctor, in Corona, Cal., informing him of the

death message. Maj. Ashton was the closest friend young Riedeman

had in Bilibid prison in the Philippines where both were held

prior to Riedeman's transfer to Japan.

Maj.

Ashton, who was among the Americans liberated in the Philippines and returned

to this country, paid Watertown a visit in August, calling at the Daily Times, following a prior exchange

of correspondence.

Maj.

Ashton is the last man who has been located who saw Riedeman alive. That was

last December 12. At that time Riedeman was ordered transferred to Japan. The

transport on which he was taken was attacked and sunk and since he did not die

until Jan. 30 of this year, as now officially revealed, he was among the group

who survived that disaster and was sent on another transport later, on which he

died.

Intestinal Inflammation

The

term "acute enteritis" which was used in the war department message as

the cause of death is a medical term for inflammation of the intestines.

Maj.

Ashton at the time of his visit in Watertown said that when he last saw

Riedeman he appeared good shape, though the improper diet which all prisoners of

the Japanese were forced to subsist on had left its mark.

Riedeman

was one of the brave band of Americans who fought against overwhelming odds on Bataan and Corregidor which

fell to the Japanese on April 6, 1942 (webmasters note: believe this should be

April 9). Previously he had been stationed at Fort Knox before he went overseas

with Co. A,

192nd Tank Corps.

His

capture, like that of the rest of the gallant band, was veiled in mystery until

In the

interval his family wavered between hope and despair regarding his safety and

the possibility of his return. Then, early this year, when word came from his

friend, Maj. Ashton, the family's spirits were considerably buoyed up and every

day word was awaited that he had been among the Americans freed, but that word

never came.

Message Misinterpreted

Some

weeks ago, after the capitulation of Japan, it was reported that Riedeman was

alive in Japan, but it was later developed the message had been misinterpreted,

that his family had merely been notified it could send a message which would be

delivered to him at the nearest possible liberation center if he was among

those who turned up.

When

Maj. Ashton was in the city he brought with him several articles belonging to

Riedeman which he turned over to his mother.

Among these was an identification tag which he had made, a book, a flag

and several carvings. Maj. Ashton had also brought to this country a diary

which Riedeman kept in Bilibid prison and which was turned over to the war

department and then sent to the Riedeman home here.

Maj.

Ashton said at the time he regarded Harvey like a brother, since the two had

been very close friends and had worried together in prison. He said he found

him resourceful and competent, a young man of exceptionally fine character who

bore up well under the hardships and humiliation at the hands of the

Japanese. He said Riedeman had assisted

him in his work at the prison, taking care of the records and issuing supplies.

Born in Milwaukee

Riedeman

was born in Milwaukee

Riedeman

was born in Milwaukee

He

attended Lincoln school and graduated from Watertown High school on

He was

later employed as a messenger and clerk by the Farmers and Citizens Bank, a position

he held for two years, prior to entering service on January 27, 1941, at Fort

Sheridan, Ill.

Incidentally,

Arthur Hilgendorf, a close friend, entered service with him the same day and

was today notified by the Daily Times

of his friend's death. Hilgendorf was enroute to Texas today from Scott Field

where he has been stationed.

Riedeman

was transferred to Fort Knox, Ky., on

After

the fall of Corregidor he was listed as captured on

Besides

his parents, he is survived by a sister, Lorraine

Riedeman, this city. He also has a grandmother, Mrs. Louise Glaus, living

in Milwaukee.

He was

a member of St. Mark's Lutheran Church here.

Cross-References:

No 1: Men of the 192nd Tank Battalion

Company B Sgt. Harvey Herbert

Riedeman was born in Milwaukee on August 17, 1918, to Mr. & Mrs. Erick A.

Riedeman. He grew up at 746 West Main

Street in Watertown, Wisconsin and attended Lincoln School. He was a 1936 graduate of Watertown High

School.

On

January 27, 1941, Harvey was inducted into the U. S. Army. He was sent to Ft. Sheridan, Illinois and

next sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky for basic training. His hometown newspaper reported that he was a

messenger and clerk for the Farmers and Citizens Bank in Watertown before being

inducted into the army.

Upon

arriving at Ft. Knox, Harvey was assigned to the 192nd Tank Battalion which had

been formed from National Guard units from Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio and

Kentucky. It was during his basic

training that Harvey became friends with Ed DeGroot.

After

basic training, Harvey was assigned to A Company, 192nd, which had originated

as a Wisconsin National Guard tank company from Janesville. After being assigned to the company, Harvey

and Ed became good friends with Sgt. Owen Sandmire.

In the

late summer of 1941, Harvey took part in maneuvers in Louisiana. It was after these maneuvers, on the side of

a hill, the he and the other members of the battalion learned that they were

being sent overseas.

Harvey

and the other men, who were shipping out, were given leaves home to say goodbye

to their families and friends. He then

returned to Camp Polk, Louisiana and rode a train to San Francisco. Upon arriving there, he and the other men

boarded a ferry that took them to Angel Island.

Harvey

sailed for the Philippine Islands arriving on November 22nd, Thanksgiving

Day. A little over two weeks later, on

December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Ten hours later, he and the other tankers

lived through the Japanese attack on Clark Air Field.

For

the next four months Harvey fought to slow the Japanese conquest of the

Philippine Islands. On April 9, 1941,

Capt Fred Bruni informed A Company that Bataan on been surrendered to the

Japanese. It was on that day that Harvey

became a Prisoner of War.

From

Mariveles at the southern tip of Bataan, Harvey started what became known

as the death march. He made his way to San Fernando. From there, he rode a train to Capas where he

and the other POWs disembarked. He then

walked the last few miles to Camp O'Donnell.

It is

not known if Harvey went out on a work detail, but it is known that he was sent

to Cabanatuan after the new camp opened.

He was later sent to Bilibid Prison where he became friends with Dr.

Paul Ashton. Harvey worked as an aide to

Dr. Ashton and kept records and issued supplies to the POWs. During his time at Bilibid, Harvey kept a

diary. After the war, his dairy was

given to his family.

In

late 1944, the Japanese began evacuating POWs to Japan or another occupied

country. Their reason for doing this is

that they did not want the men to be liberated by the advancing American

forces. On December 15, 1944, Harvey, along with 1619 other POWs were

marched from Bilibid to the Port Area of Manila, The POWs were boarded on the "Hell

ship" Oryoku Maru which was bound for Japan.

The

Oryoku Maru came under attack by American planes. The attack on the ship lasted two days

resulting with the ship being intentionally grounded and then sunk by the

planes on December 26, 1944. Harvey and

the other survivors swam to shore near Olongoa, Philippine Islands. He did this while under Japanese machine gun

fire.

While

the Japanese attempted to recapture the POWs, the prisoners were rounded up and

held on tennis courts. After all the prisoners

were back in custody, the Japanese asked if any of the POWs were too weak to

continue the voyage to Japan. Those who

said that they were too weak to go on were loaded onto trucks and taken to the

mountains. They were never seen again.

The

remaining prisoners were taken by train to San Fernando and then returned to

Manila where they boarded another "Hell Ship" the Enoura Maru. On this ship, the POWs were held in three

different holds. Men who attempted to

get fresh air by climbing the ladders were shot by the guards.

The

POWs on the ship were taken to Formosa.

There, Harvey once again came close to death when the ship was bombed

and sunk by American planes on January 13, 1945, while it was still docked. During the attack, a bomb exploded in one of

the ship's holds. This explosion resulted in the deaths of many POWs, including

Lt. Leroy Scoville, of A Company, who was wounded by the bomb.

On

January 14, 1945, Harvey was boarded onto his third "hell ship" the

Brazil Maru which left Formosa and arrived in Moji, Japan, on January 29,

1945. Of the original 1619 men that

boarded the Oryoku Maru, only 459 of the POWs had survived the trip to Japan.

Harvey

may have been wounded when the bomb exploded in the hold of the Brazil Maru,

since he was taken to Moji POW Hospital.

According to the final report on the 192nd Tank Battalion written by 1st

Lt. Jacques Merrifield, Sgt. Harvey H. Riedeman died on February 4, 1945, at

the Moji

POW Hospital in Moji, Japan. The

official cause of death was listed as dysentery.

After

Harvey died, his remains were cremated and he was buried in the Charnel House

at Moji. It is known that the Japanese

combined the ashes of the POWs buried in the house. After the war, his family requested that his

ashes be returned home to Watertown where they were buried in Oak Hill

Cemetery.

After

Harvey died, his remains were cremated and interred in the Charnel House at

Moji. The Japanese combined the ashes of

the POWs who had died. After the war,

Sgt. Harvey H. Riedeman's remains were interred at the Yokohama Commonwealth War Cemetery.

This is a British Military Cemetery.

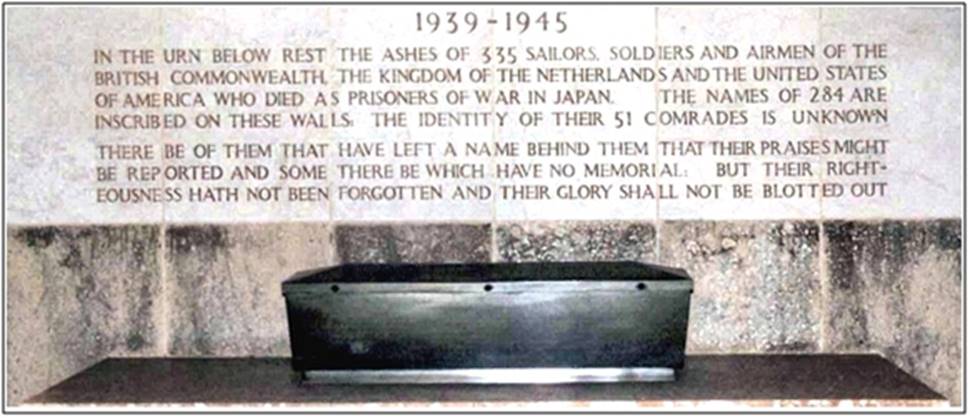

The urn contains the remains of 335 British, Australian, Dutch and

Americans who died while POWs. On the walls of the memorial, appear the names

of the POWs whose remains are contained in the urn.

click

to enlarge

Original grave where the ashes of Harvey Riedeman

and 301 other POWs were buried in at Moji Hospital in Japan.

Photo

below is of the urn that contains the remains of Sgt. Harvey Riedeman at the Yokohama Commonwealth Military Cemetery

in Japan. Since most of the remains in

the urn were British Commonwealth soldiers, the urn was relocated to a British

Cemetery after WW II.

At

some point, Harvey's family also had a memorial dedicated to him at the Oak

Hill Cemetery in Watertown, as seen at top of this page.

Set of Images

while at Fort Knox:

Riedeman

and friend Sandy (l-r)

WHS_005_713

Friend

Sandy & Riedeman WHS_005_714

Friend

Sandy & Riedeman

WHS_005_715

Riedeman WHS_005_716

Riedeman WHS_005_717

Riedeman WHS_005_718

![]()

History of Watertown, Wisconsin